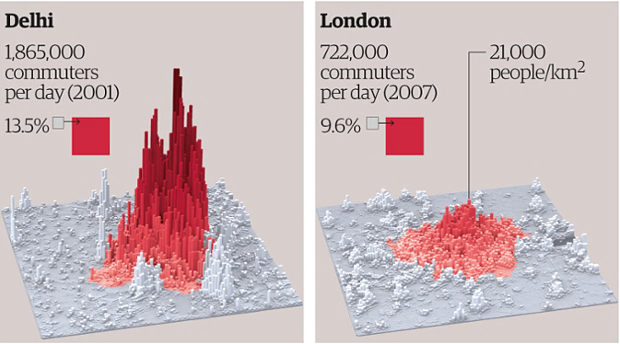

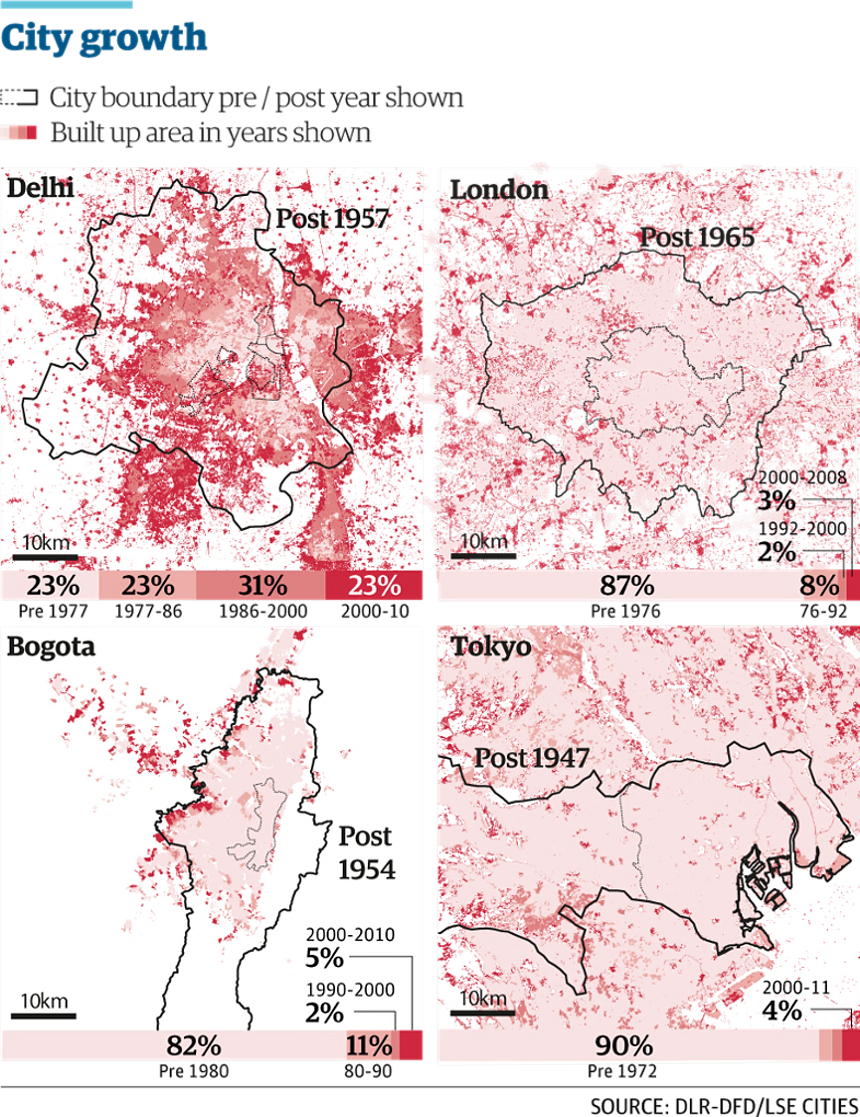

Cities are not static. Like living organisms they change and adapt over time. Some grow and others shrink in response to economic, political and environmental shifts. But they do this in radically different ways, reflecting local responses to regional, national and global changes. Recently, LSE Cities focused on the patterns of growth, governance, transport and density of the four national capitals of Japan, India, Colombia and the UK. Together, the metropolitan areas of Tokyo, Delhi, Bogotá and London have over 80 million residents (equal to the population of Germany) and, according to the Brookings Institution, a combined GDP of $2.2 trillion, the size of the Brazilian economy or three times that of Saudi Arabia.

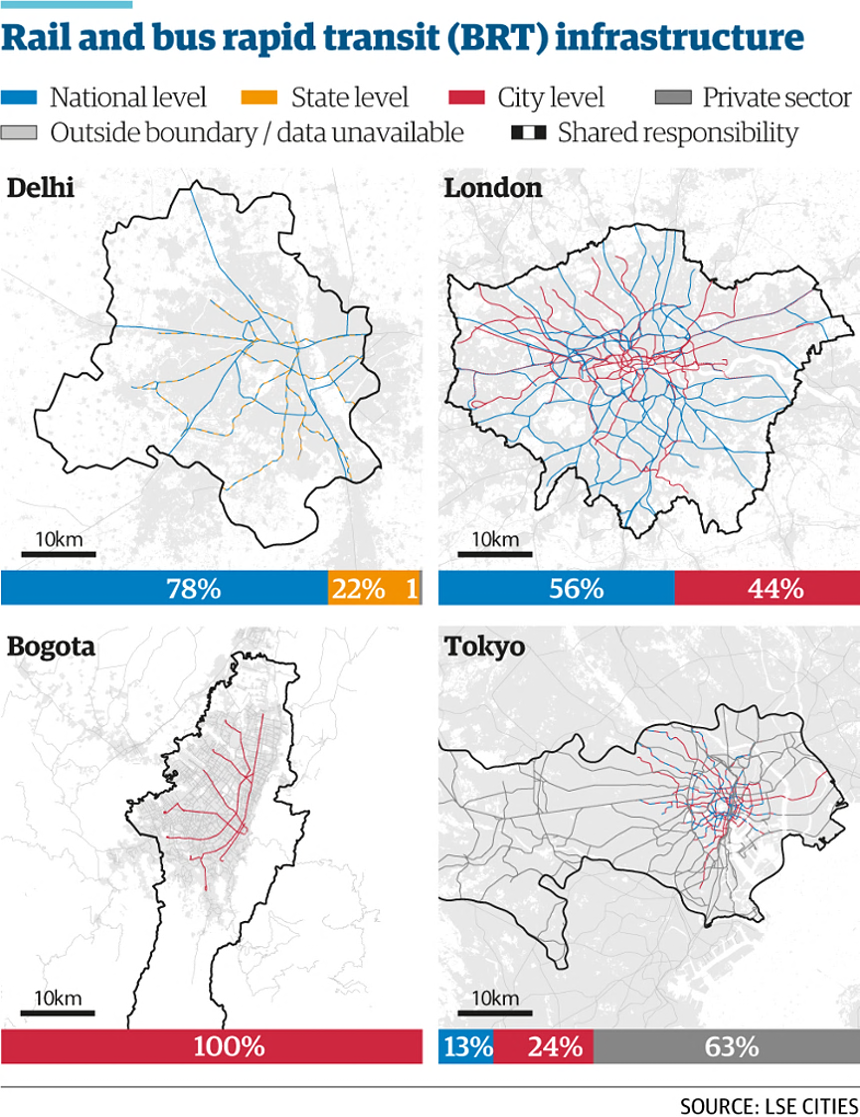

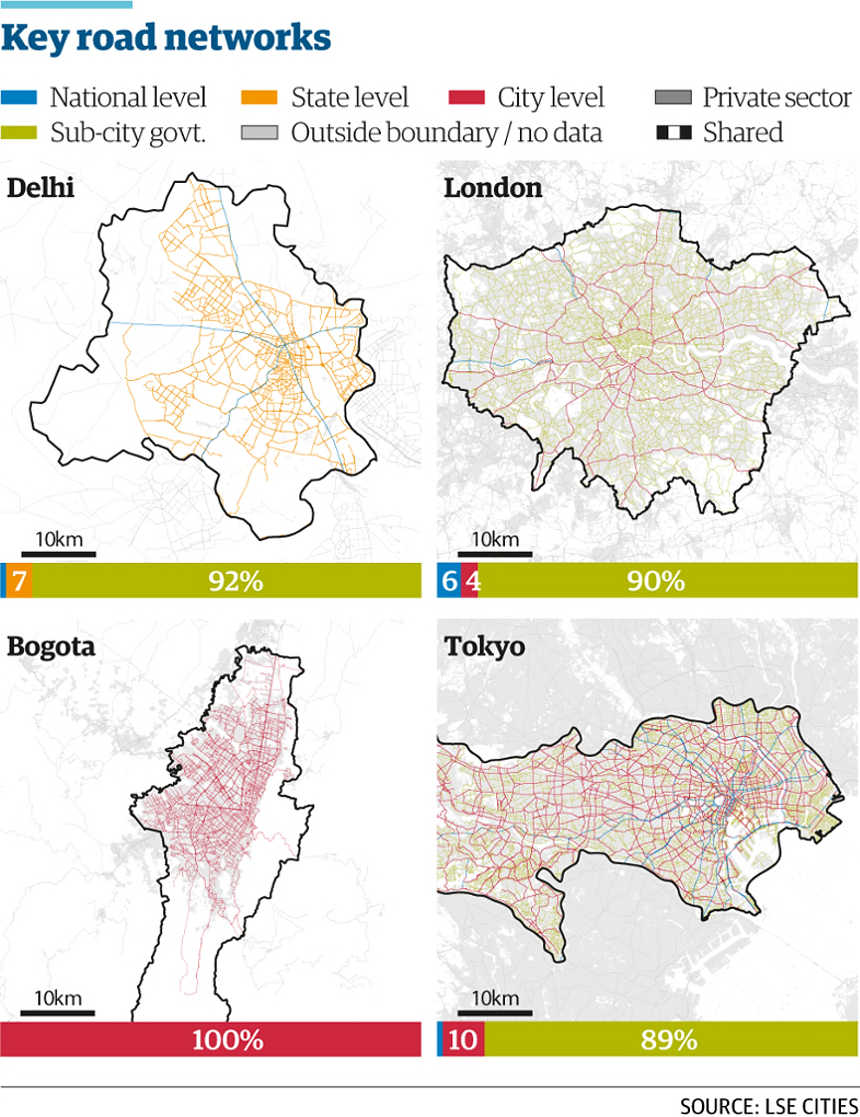

Tokyo has become a highly efficient global megacity in the last four decades – but despite its enviable integrated public transport system and the forthcoming Olympics in 2020, the city is likely to lose 400,000 people over the next 15 years as a result of low-birth rates and a slowing national economy. London, by contrast, has just come out of the demographic doldrums – overtaking its historical high of over 8.6 million (its size in 1939) and riding high on its global economic pulling power (it has just come top of the Mori Memorial Foundation index of city ‘magnetism’). Such levels of growth are fuelled by a dynamic birth rate (twice that of Rome or Madrid) and strong in-migration attracted to London’s resilient economy, promoted aggressively by its proactive mayors.

The Colombian capital of Bogotá, with a city population slightly smaller than London at 8 million, has built on the intelligent policies of successive mayors to cope with typical Latin American patterns of informality, violence and unregulated growth. Famous for introducing the Transmilenio Bus Rapid Transit and an extensive system of cycleways (ciclovías, which predate Boris bikes by a decade), Bogotá is seen as a regional exemplar (alongside Medellín) on how to manage urban change. Despite being, or perhaps because it is, the capital of the world’s largest democracy, Delhi is still struggling to find a political voice. After pioneering efforts by the former chief minister to build a metro system and introduce natural gas to its buses and rickshaws, the metropolitan area of more than 23 million people has witnessed a sharp increase in inequality even though it remains one of the safest megacities in the world, with 2.7 homicides per 100,000 people compared to Bogota’s 16.1.